James Henry Lane

2nd great-granduncle of Dorotha Piechocki's husband Jerry Piechocki

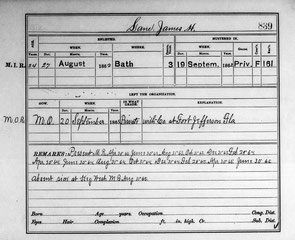

Private Co. F 161st New York Infantry

Dates of Service: 27 Aug 1862 - 20 Sep 1865

James Henry Lane, born Sep. 11, 1838, in Cayuga Co., New York, was the oldest child of four born to Jesse Isaac Lane and Maria Rogers Lane. By 1849, Jesse had moved his family to Bath, Steuben Co., New York where he farmed. At the age of 24, James enlisted at Elmira, Chemung Co., New York, Aug. 27, 1862, for a period of 3 years, with $100 bounty paid by the town.

By late May, with nearly 40,000 men at hand, General Banks felt it time to attempt the capture of Port Hudson. The troops were ferried across the Mississippi to make their efforts on the east side of the river. Grant had been in front of Vicksburg for months and Banks was hoping to avoid a siege with a “quick kill” but the town and fort were already alerted by the Union navy steaming past the week before.

As the army marched up the road to Port Hudson, they came upon a sign that read "Beware Yankees! This road leads to hell!" The troops were not served well by their officers. General Banks ordered an all-out assault for the morning of May 27 but informed none of the four attacking forces of a time nor did he make any preparations pertaining to the obstacles the charging troops would encounter. The result was two groups attacked in the morning and two attacked in the evening. Both assaults were thrown back with heavy losses. One Federal officer claimed "the affair was a gigantic bushwhack." After that the troops dug in and prepared for a siege just like at Vicksburg.

While participating in the siege General Banks received word that Fort Butler, a Union fort near Donaldsville, was under attack by a large Confederate force. Gen. Banks was compelled to send a relief column to aide the fort. Unknown to Banks was that the assault on Fort Butler had failed and the enemy troops were moving in the direction of Port Hudson.The 161st and the 1st Brigade were sent out. On June 28th, 1863, six miles outside of Donaldsville, the Brigade met with enemy resistance. The 161st drove the skirmishes back and proceeded to drive them for a few miles. The Regiment was then ordered to halt as they came upon a very large body of the enemy. This turned out to be the entire Confederate assault force from the failed Fort Butler attack. The Brigade was drawn up with another to its right (Weitzel’s Brigade). Artillery on both sides were cutting down the men as they traded volleys.

The following first-hand accounts of the 161st NY Vol. Inf. come from contemporary newspaper clippings:

Lt. O.M. Smith tells the rest in his letter home:

“About noon the rebels in strong force attacked our position.—Weitzel, on the other side, having no artillery, retreated, leaving our men exposed to a cross fire, which was said to have been terrible.—Our boys of the 161st fought well, and not a man left the ranks to skulk, while the 30th Mass., an old Reg't, broke and run. Finally the battery which our regiment was supporting, left, and then the rebs got close on to us, when we raised and fired, making then retreat. Then we had to help the Artillery out of the mud, &c., and the rebs came back again; being Texans, all mounted, the order was given for our regiment to fall back, and our's was the last to leave, as it was the first to advance. We had to retreat back to Donaldsonville, pursued by the Texans on horses. Our Regiment has suffered badly, losing 77 men killed and wounded. Our company lost the most, having 2 killed and 7 wounded.”

Another account of the action by an unknown reporter was taken from a NY newspaper:

“The enemy were in heavy force in front of us, had attacked the small force here in Fort Butler and were severely repulsed. On the 12th inst. three regiments of our Brigade moved down the Bayou on the north side while Col. Morgan moved along the South. We found the enemy in force in about a mile and drove them about four miles, when we encamped. We fared sumptously [sic] on chickens, sweet potatoes, green corn, tomatoes, melons, &c. At noon of the 13th we were attacked by the enemy in heavy force on both sides of the Bayou, and Col. Morgan commenced a retreat on the south side. This left our flank exposed, and the enemy poured heavy fire into us from the levee opposite of us, and at the same time a heavy force of mounted men commenced to flank us on the right. The brigade were ordered to fall back, and the 161st covered the retreat. We fell back for five miles fighting all the way, most of the time under a flank fire from under the levee opposite, and a part of the time we were flanked on both sides, the enemy following so closely in our rear. Our men fought bravely and manfully. Scarcely a man faltered, but moved through a raking fire in almost as perfect a line as when on parade. We made a dozen halts, and then would pour into the enemy our fire, check them for several moments, and then slowly move on in line of battle. Our loss was heavy. Seventy-three men out of about two hundred and fifty were killed, wounded and missing. The loss in our Company was seven—three killed, two wounded, and two taken prisoners.”

The Division returned to Port Hudson and continued taking turns on the front line during the siege. In a letter home, William E. Jones writes of the horrors of the continued siege as the weeks go on:

“Oh, the sufferings of our wounded soldiers! Enter the Hospital I have already spoken of. The whole space is being rapidly filled up.—At your right lies a man whose left knee has been completely shattered by a cannon ball; he is rolling in agony and calling for help.—By his side you see a Colonel, wounded in the lungs, and quietly breathing away his life. A little farther on, passing by several others, you come to another, sitting up, mortally wounded, but not aware of it. Behind him to the right, is Col. Cubby, badly wounded in both arms; and, to the left, a Major, with a very pleasant countenance, who appears to be sleeping the sleep of death. Close by you, as you turn to the left, is a young man sitting against a tree, and held by two others, while the Surgeon amputates some of the fingers of his right hand; the perspiration is rolling off him in streams, and his screams thrill you. Near him a very young lad attracts your attention by his loud crying and the entreaty, 'Oh, Doctor, Doctor, don't use the knife,' while in the centre of the group are the amputation tables, from which some of our brave fellows are to go forth cripples for life. One of the saddest scenes painfully impressed upon my mind, was that of a father kneeling by the side of his dying son, with one hand fanning his child, and with the other brushing away the big tears that rolled down his own cheeks.”

Due to the heat both sides were succumbing to disease, heatstroke and dysentery.

After twelve grueling weeks which featured bombardment by land and ship, General Banks felt that the siege had lasted long enough and on June 14th launched another all out attack. Although by now the Union troops outnumbered the Reb defenders by four to one, the defenses of the fort and town were so strong as to result in yet another bloody repulse. With 4,000 dead and another 7,000 down sick the siege had to continue. One last assault was planned for July 8th. Four volunteer groups of 1,000 men each were scheduled for a surprise morning attack by blowing up mines in the defenses and charging through. The 161st and two other regiments were to figure dominantly in the followup attack. Two days before the planned attack news came that Vicksburg had fallen and a cease fire was declared. The fort was surrendered on July 9, 1863. A soldier from the 161st wrote the following about the surrender:

"On Thursday morning Gen. Banks, accompanied by his staff and two batallions [sic] of the 'stormers,' entered the rebel works at Port Hudson, and took formal possession of them. The rebels numbering about 3,800 were drawn up in line, and stood at order arms, as Gen. Banks and the stormers marched past them until our right arrived opposite their left, when our men were fronted and came to an order arms. The rebels then received the order from Gen. Gardner to ground arms, which they did, some of them throwing their guns violently to the ground. I should have stated that the stormers were headed by the excellent brass band of the 116th New York, and as they entered the 'sallyport,' struck up 'Yankee Doodle,' followed by 'Hail Columbia,' the 'Star Spangled Banner' and the 'Gem of the Ocean'. A battery of Artillery followed close upon the heels of the stormers, and just as the rebels had ground their arms, the Stars and Stripes were floating to the breeze in different parts of the fortification and the battery commenced firing a full national salute. By this time several regiments near the 'sally port,' commenced crowding into the works and as the dear old flag proudly floated from one flag staff after another, such a shout as those stormers and regiments sent up, was perfectly deafening, and would have thrown a genuine Copperhead into 'coniption [sic] fits.' It was a proud hour for Gen. Banks and his gallant soldiers, but the butternuts looked on with stoical indifference."

After Port Hudson, General Banks with the 12,000 men he had on hand decided the 19th and 17th Corps, including the 161st, would go into Louisiana and up the Red River with plans to drive Confederate troops out of Louisiana. Things were going fairly well, The 17th Corps had marched deep through Louisiana burning crops and freeing contraband slaves, meeting little resistance until they were 150 miles in. At this point, on April 8,1864, the Union troops were met by Confederate Cavalry at Sabine Crossroads. While it was simple to drive horse troops back, no one noticed the ambush that had been prepared. Confederate troops, under General Richard Taylor, struck on the front and both flanks of the 19th Corps and the lead 3rd Division, driving the Union lines back in a rout. The 161st and the 1st Brigade held their ground allowing time for the entire division to reform and fight off the next attack. The Union forces lost 2,235 men while the Confederates less than 1,000.

When the evening came Banks decided that the Union forces could not hold with enemy reinforcements approaching and they fell back to the location of Pleasant Hill, some ten miles away, during the night. The next morning, the reinforced Confederate Army charged up a fortified Pleasant Hill, first on the left and center, the fighting being mostly in open field, where the combatants could see each other and be distinctly seen by the enemy. The attacking Confederate lines wavered, then were broken in pieces by the heavy volleys and fell back. When the enemy struck the inner defensive line, they received its heavy volleys, fell back and massed its forces on the Union right; they were met and hurled back by the 161st and again retired before the stubborn resistance of the veterans of the Nineteenth army corps. After two hours of failed attacks the Confederates had enough. The need for water and rations had become a serious one and General Banks decided to fall back to Natchitoches to reorganize their units. At this point, Admiral Porter had returned with the transports of the army and the troops were making plans to leave when the Rebels then re-formed and attacked simultaneously the right flank and centre, meeting the steady volleys of the Union men and were again repulsed. The firing of the enemy during this attack was most severe. The enemy again re-formed, and, with reinforcements, attacked the left flank and center with increased determination; but after what must have seemed like an eternity, in which the lines did not move, they were once and for all repulsed. The fire of Emory's division during this whole contest was fearful, and its effect most withering, as was attested when, ”in the quietness of that night, from one end of our line to the other, the groans of their wounded and dying told of the fearful sacrifice they had made.” The enemy lost fifteen hundred killed and wounded in this engagement, the Union lost 1,369.

The After Action report stated the following: "The conduct of the division during this terrible contest, is worthy of the highest praise. Coming to the field to meet an army corps and several thousand cavalry, with their trains in full, panic-stricken retreat, they preserved their coolness, re-formed their broken ranks under a heavy fire, encountered an elated and victorious enemy, checked and finally repulsed him, and the sun went down upon a defeat suddenly changed to a victory, and the army which an hour before was threatened with destruction was saved. With such troops, disciplined to obey directions, under all circumstances, victory is sure, and the humiliation of the enemy is certain.” This is debated by historians today since the Union men boarded the wounded on the transports and marched back to Baton Rouge, leaving the field and the momentum to the Confederates.

At this time the 3rd Brigade and 161st was relegated to the capture and the posting of men in small towns throughout lower Louisiana. Occasionally, they would join forces with a Division and make a sortie into areas where larger concentrations of Confederates were thought to be. The largest of these was at Mansura where Confederate General Richard Taylor attempted another surprise ambush. This resulted in a large artillery duel that lasted several hours. After it appeared that the Rebels were running low on artillery shells, the division massed for their own flank attack. Discretion being the better part of valor, Taylor removed his guns and left the field of battle.

The was the last real action the 161st participated in. After a few more sorties into Louisiana the 161st and the 3rdBrigade were transferred to be reserves in the campaign to capture Mobile, Alabama. The Regiment wintered in White River, Arkansas, and then boarded the transport "John H. Dickey" for a trip down the Mississippi River. One last adventure awaited James and his regiment as their ship met the steamer "John Raine."

“The most unfortunate occurrence of our trip thus far, is yet to be related. We were compelled to remain at Vicksburg several hours to coal up, and did not leave there until late in the afternoon. We had got fairly under weigh and had made about ten or fifteen miles, every one on board being in the best of spirits, the boys contented, then suddenly crash! crash! went one side of the John H. Dickey, knocking everything concave. The utmost excitement and consternation prevailed on deck and in the cabin. Some imagined the boiler had bursted, others, (novices,) that the guerillas were shelling us, while many were too much frightened to form any opinion about the matter. In the cabin the stampede was tremendous. Fright overcame every other consideration and each one's sole aim seemed to be to look out for No. One. Many of our boys were quartered on the hurricane deck. Guns, knapsacks, straps, cartridge boxes, &c., &c., were swept overboard in the twinkling of an eye, and many a poor fellow lost all he had except what was on his back. Men jumped overboard, and those that were not drowned swam to the shore. The cause of the accident was a collision, the John Raine running into us striking our boat amidships.

You will see in Harper's illustrated newspader [sic] a sketch of the burning of the boat on the 8th, and also of the collision, made by Lieut. [George] Slater, of Co. C, in a reasonable time. I am particularly indebted to Lieut. John Laidlow also of Co. C, for the following particulars of the casualties. This makes a total of twenty-three wounded and three drowned of the 161st N. Y. V. Many others were slightly hurt by being run over and trampled upon, but their injuries are not sufficiently serious for public mention.” - Correspondence of the Elmira Advertiser

Caption: "Mississippi River steamboat wrecked with the 161st on board, many lost." On reverse: "Drawn by ... Geo…" [prob. Slater]

The troops were picked up on the shore without equipment and then transported to Florida where they mustered out of the service. [Notice James was "absent sick at Key West, MR (muster roll) Aug 31st 65"]

Following the war, James returned to his father's home in Bath, New York. By 1865 Jesse had moved with his wife Maria, grown children, James, Delos and Nancy, to Wayland, Allegan Co., Michigan, where they began farming. In 1867 James and his wife Mary Ann Abel had a daughter, Dora, born November 20, 1867, in Allegan. In 1872, the couple had another son, Henry J., and in 1880 a son Fred E.

Mary Ann had died before 1898, when in July James married Emma A. Smith Morse in Battle Creek, Calhoun, Michigan. She was a divorcee with three children. James and Emma lived in the village of Wayland, Allegan Co., in 1900, with his 20-year old son Fred and Emma's 13-year old daughter Edna. James and Fred found work as day laborers. By 1910 James, Emma, Fred, and Emma's granddaughter Alwilda Farrah were living in Wayland Township, where James farmed his own place.

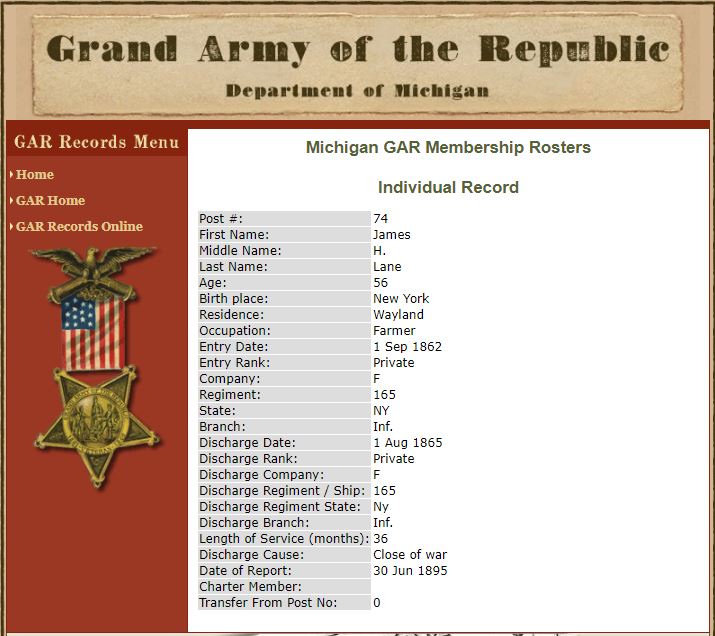

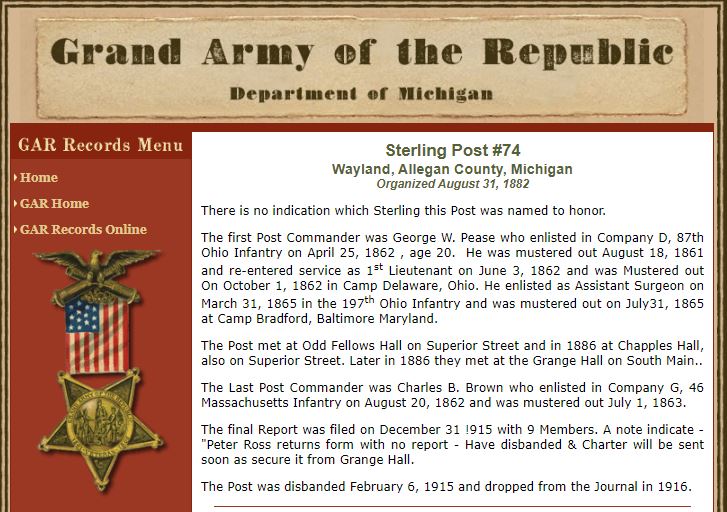

James was reported on June 30, 1895, as a member of the Sterling Post #74 GAR in Wayland, Allegan, Michigan.

At age 66, James first applied for admission to the Michigan Soldiers Home in Grand Rapids, Michigan, October 7, 1904, on disability from "age and loss of eye sight." He stated that he was receiving a pension of $12 per month. The surgeon's certificate confirmed that he had "loss of sight of right eye, impaired vision in left [eye], rheumatism and general debility." On September 6, 1917, James applied for readmission to the Soldiers Home on cause of "old age," stating he was then receiving $30 per month. The surgeon's certificate with this application noted the veteran was suffering from "chronic disease of liver and old age." On February 7, 1918, he was readmitted a third time. None of the Soldiers Home records indicate whether or how long he may have been treated there. However, on November 18, 1920, James Lane died of chronic myocarditis at the Michigan Soldiers Home in Grand Rapids, Michigan, where he had been attended by the certifying physician since November 1, 1920.

James H. Lane was buried in Elmwood Cemetery, Wayland, Allegan, Michigan, where his parents, his brother Delos and sister Nancy all rest.

ADDITIONAL SOURCES: Ancestry dot com; wikipedia; nps.gov; fold3; findagrave; Shelby Foote “The Civil War”; Time-Life “The Civil War”; civilwartalk.com

GRAVESITE: Elmwood Cemetery, Wayland, Allegan, Michigan

Written by Jerry and Dorotha Piechocki, May 2020